Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

-

News

-

Editions

-

- Lists

-

Viewpoints

-

HBJ Events

-

Event Info

- 2024 Economic Outlook Webinar Presented by: NBT Bank

- Best Places to Work in Connecticut 2024

- Top 25 Women In Business Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Family Business Awards 2024

- What's Your Story? A Small Business Giveaway 2024 Presented By: Torrington Savings Bank

- 40 Under Forty Awards 2024

- C-Suite and Lifetime Achievement Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Health Care Heroes Awards 2024

-

-

Business Calendar

-

Custom Content

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- April 29, 2024

- April 15, 2024

- April 1, 2024

- March 18, 2024

- March 4, 2024

- February 19, 2024

- February 5, 2024

- January 22, 2024

- January 8, 2024

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

HBJ Events

Event Info

- View all Events

- 2024 Economic Outlook Webinar Presented by: NBT Bank

- Best Places to Work in Connecticut 2024

- Top 25 Women In Business Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Family Business Awards 2024

- What's Your Story? A Small Business Giveaway 2024 Presented By: Torrington Savings Bank

- 40 Under Forty Awards 2024

- C-Suite and Lifetime Achievement Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Health Care Heroes Awards 2024

Award Honorees

- Business Calendar

- Custom Content

Gov. Lamont’s executive orders have helped CT beat back COVID-19, but some businesses want to curtail his powers

HBJ Photo | Steve Laschever

Small business owner Luis Ramirez is suing Gov. Lamont over pandemic shutdowns. He’s not alone.

HBJ Photo | Steve Laschever

Small business owner Luis Ramirez is suing Gov. Lamont over pandemic shutdowns. He’s not alone.

When Gov. Ned Lamont announced in May that he would force Connecticut nail salons — shuttered by his own order since COVID-19 struck the state in March — to wait another month to reopen, Luis Ramirez was at his wit’s end.

The owner of Roxy Nails Design in Hartford’s Frog Hollow neighborhood, Ramirez had scraped together $800 for safety improvements to his salon, even with overdue rent piling up, as he anxiously prepared for what was supposed to be a May 20 return to business.

However, with 11 days to go, Lamont changed course, keeping nail salons closed until June 17, citing concerns they weren’t ready to safely reopen.

“I was like ‘wow, how could this happen?’ ” Ramirez recalled in a recent interview about the unexpected delay. “We were spending our savings. We thought we would lose our business after five years of work.”

Ramirez, who is back open and fighting to make good on his missed rent, is now suing Lamont in state court, alleging that the governor’s business-closing executive orders during the pandemic have been arbitrary and unconstitutional.

Indeed, over the past four months, Lamont has exerted extraordinary unilateral powers that many businesses and residents likely never knew he possessed.

His actions have helped Connecticut become a leading state in controlling the virus, earning him praise from the Connecticut Business & Industry Association (CBIA), and only moderate criticism from Republican lawmakers.

The public has also been impressed. A May Quinnipiac University poll found Lamont’s approval rating was 65%, the highest for a Connecticut governor in over a decade. More than three-quarters of voters said they approved of his handling of the pandemic.

But not everyone is happy.

Besides Ramirez’s challenge, there have been at least five other lawsuits filed in recent months by Connecticut business owners — from residential landlords to gym, bar, spa and tattoo parlor operators — alleging Lamont has overstepped his legal bounds and damaged their interests in the process.

The lawsuits add to a growing number of similar complaints in more than a dozen other states where governors have leveraged their respective emergency powers during the pandemic.

If successful, the Connecticut lawsuits threaten to curtail Lamont’s ability to respond if a second wave of the virus hits the state — something that’s now happening in places like Texas, Florida and Arizona, which reopened their economies on more aggressive timetables.

Businesses pursue injunctions, damages

While Ramirez’s Park Street nail salon is back open, its short-term survival isn’t guaranteed.

Besides the overdue rent, customer traffic isn’t back to normal, partly because several salon employees have left, forcing Ramirez and his wife, Rosiris, to staff the store alone.

Salons are also currently limited to 50% capacity and appointment-only customers.

“It’s been really tough,” Ramirez said. “If we had been able to open in May, it would have been a big difference.”

Ramirez’s case has drawn interest from afar. Steve Simpson, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation — a California libertarian-leaning outfit that represents individuals against what it views as unlawful government policies — has taken the case pro bono, working alongside Ramirez’s local attorney.

The suit alleges that Lamont’s orders have violated the equal protection and separation of powers clauses of the U.S. Constitution, and that he violated state statute by delegating some of his pandemic decision-making to other entities, such as the Department of Economic and Community Development (DECD).

“I’m not saying the governor is a bad person here, I understand what’s going on is difficult for everybody,” Simpson said. “But he is an official who must follow the rule of law.”

If successful, the suit could restrict Lamont from ordering similar business shutdowns in the future, but Ramirez isn’t going to get a payday, no matter how things go in court. The Superior Court lawsuit seeks just $1 in nominal damages from the state — a mostly symbolic form of relief.

Simpson said it would be difficult to convince a court of a methodology for calculating damages, when so many businesses have suffered.

Still, curtailing Lamont’s authority moving forward would be a victory, Simpson said.

“[Ramirez] and I think most every other business in Connecticut is under the constant threat of another shutdown,” he said.

While Ramirez isn’t seeking damages from the state, a group of eight residential landlords and property managers that sued Lamont in June are.

That suit, filed in federal court, challenges Lamont’s executive orders that have temporarily beefed up protections for renters. They include a moratorium on evictions and extended grace periods for paying rent — from the usual nine days to as many as 60 days. Lamont also ordered landlords to divert a portion of tenants’ security deposits to cover a rent payment, if tenants request they do so.

Rep. Craig Fishbein (R-Wallingford) is also an attorney and one of several Connecticut lawyers representing the landlords in the case.

He said the executive orders have violated various clauses of the U.S. Constitution, and he called the suit’s request for damages the “appropriate thing to do.”

“Our clients have been damaged financially,” Fishbein said.

Paul Mounds, Lamont’s chief of staff, said the governor’s legal team has analyzed each executive order to ensure it fits within the scope of the emergency legal powers granted to him under state law.

“Our overall focus, first and foremost, is how we can best keep our state moving, while keeping people safe throughout a public health emergency and epidemic,” Mounds said.

He also said Lamont has taken a collaborative approach with executive orders, reaching out and getting feedback from constituencies — especially the business community — most impacted.

He noted that business leaders, including the CBIA, were on the governor’s Reopen Connecticut Advisory Group, which helped inform some of the governor’s decision-making.

Lamont also issued many directives that provided businesses regulatory relief, such as delaying tax-payment deadlines, Mounds said.

Broad emergency powers

It’s tough to make the case that Lamont has stood out among governors as a power-hungry ruler during the COVID-19 crisis, since many of his peers across the country have taken similar or even stricter measures.

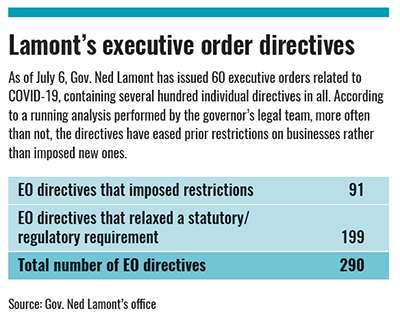

But there are some unique aspects to the Connecticut statute that underpins Lamont’s 60 executive orders (and counting), according to Hartford law firm Day Pitney, which wrote in an April white paper that Nutmeg State law grants the governor an unusually broad set of powers compared to most other states.

For example, during the six-month public health and civil preparedness emergency periods declared in March, Lamont is permitted to modify or suspend any state statute, a power typically left to the legislative branch. Many states offer “significantly narrower” emergency authority to their executive branch, the lawyers wrote.

Under the state’s emergency law, Lamont could unilaterally raise tax rates, the attorneys wrote, though the governor’s executive orders thus far have been “far more modest and do not test the full limits” of the power granted to him.

The paper concluded there are at least some constitutional doubts about those powers, including Lamont’s delegation of certain decisions to various state agencies during the pandemic.

There’s also a potential argument to be made that the COVID-19 crisis is a public health emergency, but not a civil preparedness emergency (Lamont has declared both), a distinction that could limit some of the governor’s authority.

However, there will be various factors working in Lamont’s favor if one of the lawsuits reaches a decision, said Christopher Klimmek, one of the Day Pitney attorneys who co-authored the white paper.

“The orders were responding to a very serious and genuine emergency, and they were issued promptly, with a lot of thought put into them,” Klimmek said.

Another key factor, the white paper noted, is “a strong sense, deeply rooted in American law, that the inherent power of the executive is at its apogee when confronted by an emergency.”

Klimmek said he’s been surprised by how flexible his clients and businesses in general have been in complying with the executive orders.

“We have a lot of large clients that want to be good citizens and I think it is to their credit that they are figuring out ways to work things out,” he said. “But there are plenty of litigious folks out there and the impact of these orders has been significant. We are really in uncharted legal territory. We’ve seen lots of plaintiffs challenge much less burdensome rules that have a much less legal foundation.”

Day Pitney attorney Susan Huntington said companies have another motivation to comply with executive orders: They are concerned about litigation from employees, customers or other third parties should they contract the virus at their place of business.

“They are worried about not only getting pushback from the government, but also getting sued by customers and workers,” she said.

Criticism and praise

The CBIA and National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) are two lobbies that can usually be counted on to crusade against government regulation that creates uncertainty and costs businesses money.

Less so during a pandemic.

In recent interviews, outgoing CBIA CEO Joseph Brennan and NFIB Connecticut Director Andrew Markowski each shared a few quibbles about Lamont’s pandemic performance. They both cited the reopening delay for nail and hair salons as a misstep, and Markowski argued that Lamont should have given the legislature a larger role in his decision-making process.

But on the whole, each said the governor’s executive orders largely seemed to make sense given the uncertain and unprecedented situation.

“It’s easy to find fault with anyone in a situation like we’ve been in, but on balance, what I’m hearing from most of our members is that he’s done a very good job,” Brennan said. “When you look at the level of disruption caused by this, it’s hard to imagine trying to manage through it in real time when you have almost zero time to prepare for it.”

Some CBIA members wanted to challenge Lamont’s executive orders early on in the pandemic, Brennan said.

“As the numbers kept spiking and deaths kept mounting, I heard less of that,” he said.

Markowski said he was relieved that Lamont deemed a fairly broad set of businesses as essential, allowing them to remain open.

He said Lamont seems to have based his decisions on available data and advice from medical experts.

“On the other hand, I think it’s fair to say that there needs to be a balance in terms of the decision-making process,” he added.

Rep. Mike France (R-Ledyard), chair of the legislature’s Conservative Caucus, was less kind in his review, giving Lamont a grade of “C or C+” for his handling of the pandemic.

“Certainly the numbers have been good, but I don’t think we understand what the cost of that is going to be long term for our state,” France said.

He argues that Lamont failed to adequately change his strategy when it became clearer that the virus was not likely to infect 350,000 to 700,000 Connecticut residents, which state epidemiologist Matthew Cartter had said in March was a possibility.

“I gave the governor some leeway at the beginning because there was a significant lack of information, and what information there was seemed to be like the end of the world,” he said.

Based on Connecticut’s plummeting number of daily deaths and hospitalizations, as well as the virus’ shrinking transmission rate, France said the state should be well beyond the second phase of Lamont’s reopening plan. However, he’s unlikely to get his wish, as Lamont, citing concerns about developing hot spots in several states around the country, recently decided to delay phase three, which had been slated for mid-July.

France also said Lamont’s executive orders should have treated regions of the state differently. For example, his eastern Connecticut district, which had far fewer COVID-19 cases than Fairfield County, should not have seen as extensive a shutdown, he said.

France acknowledges that state law gives Lamont broad authority, though he feels it is unconstitutional.

“We may see some remedies in court,” he said.

The basis for the story implies that Lamont did an acceptable job with his executive powers while managing the pandemic. The authors must be looking at different data than I. Connecticut suffered the loss of the highest percentage of our nursing home residents than any other State by far, 12.7%, and the deaths continue.

In terms of per capita deaths, CT comes in third worse in the USA. When the States are grouped with all the world's countries with population equal to or greater than Montana, our smallest population State, CT comes in as third worst IN THE WORLD.

His performance has been wholly unacceptable and his joining forces with the other Governors who did as badly or worse is another measure of his lack of judgement and understanding. He and the advisors he chose simply have no sense for the grief and hardship they have caused, and continue to cause, the majority of the residents of the State, or they simply do not care.

2022 Giving Guide

This special edition informs and connects businesses with nonprofit organizations that are aligned with what they care about. Each nonprofit profile provides a crisp snapshot of the organization’s mission, goals, area of service, giving and volunteer opportunities and board leadership.

Learn more

Subscribe

Hartford Business Journal provides the top coverage of news, trends, data, politics and personalities of the area’s business community. Get the news and information you need from the award-winning writers at HBJ. Don’t miss out - subscribe today.

Subscribe

2024 Book of Lists

Delivering Vital Marketplace Content and Context to Senior Decision Makers Throughout Greater Hartford and the State ... All Year Long!

Read Here-

2022 Giving Guide

This special edition informs and connects businesses with nonprofit organizations that are aligned with what they care about. Each nonprofit profile provides a crisp snapshot of the organization’s mission, goals, area of service, giving and volunteer opportunities and board leadership.

-

Subscribe

Hartford Business Journal provides the top coverage of news, trends, data, politics and personalities of the area’s business community. Get the news and information you need from the award-winning writers at HBJ. Don’t miss out - subscribe today.

-

2024 Book of Lists

Delivering Vital Marketplace Content and Context to Senior Decision Makers Throughout Greater Hartford and the State ... All Year Long!

ABOUT

ADVERTISE

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

1 Comments