Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

-

News

-

Editions

-

- Lists

-

Viewpoints

-

HBJ Events

-

Event Info

- 2024 Economic Outlook Webinar Presented by: NBT Bank

- Best Places to Work in Connecticut 2024

- Top 25 Women In Business Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Family Business Awards 2024

- What's Your Story? A Small Business Giveaway 2024 Presented By: Torrington Savings Bank

- 40 Under Forty Awards 2024

- C-Suite and Lifetime Achievement Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Health Care Heroes Awards 2024

-

-

Business Calendar

-

Custom Content

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- April 15, 2024

- April 1, 2024

- March 18, 2024

- March 4, 2024

- February 19, 2024

- February 5, 2024

- January 22, 2024

- January 8, 2024

- Dec. 11, 2023

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

HBJ Events

Event Info

- View all Events

- 2024 Economic Outlook Webinar Presented by: NBT Bank

- Best Places to Work in Connecticut 2024

- Top 25 Women In Business Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Family Business Awards 2024

- What's Your Story? A Small Business Giveaway 2024 Presented By: Torrington Savings Bank

- 40 Under Forty Awards 2024

- C-Suite and Lifetime Achievement Awards 2024

- Connecticut's Health Care Heroes Awards 2024

Award Honorees

- Business Calendar

- Custom Content

A Tale of Two Apartment Markets: Red-hot Hartford, New Haven multifamily sectors evolve along different paths

PHOTO | MICHAEL PUFFER

Developer Randy Salvatore is building new apartments in both Hartford and New Haven.

PHOTO | MICHAEL PUFFER

Developer Randy Salvatore is building new apartments in both Hartford and New Haven.

RMS Cos. is just now welcoming the first tenants to a new, sleek, gray-sided apartment building wrapping around Trumbull and Main streets just off the northern edge of downtown Hartford.

The 270-unit building next to Dunkin’ Donuts Park is among the first installments of Stamford-based RMS’ “North Crossing” development. RMS President Randy Salvatore said the plan is to eventually add about 1,000 new apartments around the stadium, largely by building on parking and other empty lots.

About 40 miles south in New Haven, RMS is nearing completion of “Pierpont at City Crossing,” a 223-unit building also erected on a vacant parking lot.

The fact that Salvatore is developing apartments in both markets isn’t wholly unique. Several developers are building new rental units in Hartford and New Haven — cities seen as critical to Connecticut’s economic future, both in attracting new talent and companies to the state.

In some ways, Hartford’s and New Haven’s multifamily markets reflect the health of their respective economies. And they are evolving in similar and dissimilar ways.

RMS’ developments in both cities focus on small units in buildings packed with premium amenities including pools, fitness rooms, lounges and more.

They differ in financing and rents. The Capital Region Development Authority (CRDA) provided an $11.8 million low-interest loan for RMS’ $56.2 million project in Hartford.

Being a CRDA-backed project also effectively cuts a Hartford apartment development’s tax burden in half for its usable life, a major advantage.

Salvatore said his New Haven project benefited from a five-year tax abatement, but otherwise received no public backing.

Developers and economic development officials said New Haven’s efforts to improve downtown livability are more advanced than Hartford’s, and that its economic engines have also more successfully linked to apartment demand.

Most see Hartford as an increasingly good bet with the potential to nearly match New Haven as an apartment destination.

For now, however, Hartford rents don’t justify the costs of putting up new apartment buildings without public subsidy.

Salvatore said he can charge $2,200 to $2,300 monthly for a one-bedroom apartment in New Haven, and about $1,800 to $1,900 per month in Hartford.

“It can be a 15- to 20-percent difference,” Salvatore said. “New Haven does not need outside public financing. … In Hartford, the rents are not at that point right now where you don’t need some of that public support.”

Even so, Salvatore believes the national trend toward city living and Hartford’s efforts to grow dining, arts and entertainment options will continue to strengthen the Capital City’s appeal — even as it struggles with higher office vacancies and fewer workers downtown due to the pandemic’s influence.

Salvatore said he’s had an overwhelming response from prospective renters at his new Hartford property, validating his plan to continue building.

He hopes to break ground this summer on the next phase of North Crossing — a $60-million development including a 530-space parking garage and 237-unit building on a single lot. Salvatore is also moving to convert the top floors of the downtown Hilton Hotel into 142 apartments.

“I wouldn’t be making these kinds of investments — taking these kinds of risks — if I didn’t believe in the future of both of these cities,” Salvatore said. “I’m very bullish on both New Haven and Hartford. That’s why I continue to build and continue to own significant real estate in both.”

Apartments beget more apartments

In Hartford, new apartment developments are seen as an economic development tool for a city that has long relied on big corporations and thousands of office workers to fuel its shops, restaurants and real estate market — a dynamic put at risk by the pandemic, which has made full- or part-time remote work more the norm.

Since its formation in 2012, the CRDA has spent $156 million backing downtown apartment builders, leveraging another $500 million in private investment, according to Michael Freimuth, executive director of the quasi-public development agency. That has brought more than 2,200 new apartments to downtown Hartford, with 500 more currently under construction, he said. Rents are rising and new inventory fills quickly.

Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin compared CRDA’s low-interest loans to apartment developers to priming a pump — a boost that will improve the restaurant, retail and culture scene, and create a self-sustaining apartment market.

“Demand is strong right now, but part of our thesis is the more we satisfy that demand now the stronger that demand will be long term because people attract people,” Bronin said. “The more units you create, the more feet on the street, the more restaurants and bars open, the more quickly that turns into a virtuous circle that drives demand in a sustained way.”

In Hartford, that cycle was gaining momentum before the COVID-19 pandemic dealt a crippling blow to the retail and restaurant scene. Foot traffic in shops and restaurants has picked up, but nowhere near pre-pandemic levels. Many employers are shedding office space and allowing staff to work from home at least part of the week.

“The change in the nature of work and the fact it will probably be quite a few years before our office buildings are filled five days a week makes it that much more important to keep our foot on the gas when it comes to residential development and residential density,” Bronin said.

Bronin is hopeful the change in work habits might carry hidden benefits. As people are no longer tethered to the office, more might turn to Hartford as an affordable alternative to Boston, New York or other expensive metro areas, he said.

Victor W. Nolletti — executive managing director of investments for Institutional Property Advisors, a division of Marcus & Millichap — said CRDA-backed apartments are key to keeping and growing the number of residents in Hartford’s downtown core. That, in turn, has helped make up for some of the reduced office crowd and expanded retail and restaurant traffic beyond the traditional work day.

“You need the multifamily before you can expand the rest,” Nolletti said. “You can open up all the retail you want, but you need to have the bodies there to support it.”

How many apartments can Hartford absorb?

The CRDA was formed with a target of adding 3,000 apartments to downtown Hartford. The agency’s practical planning goal is about 5,000. Freimuth said it’s possible the city could absorb even more. Apartment developments that have come to market in recent years have occupancies above 90%, he said.

“From the market dynamics I see, I don’t think we are anywhere close to exhausting that demand,” Freimuth said.

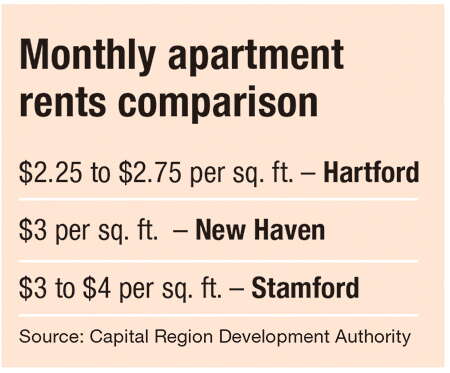

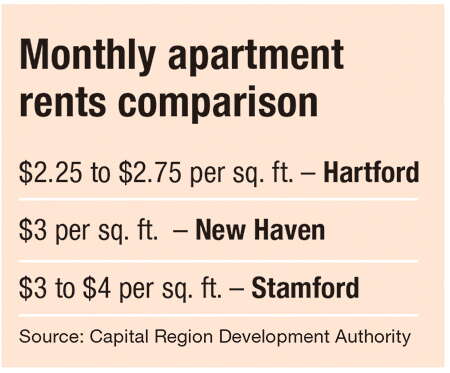

Monthly apartment rents in downtown Hartford have climbed from $1.50 to $1.75 per square foot a decade ago to about $2.25 to $2.75 per square foot today, Freimuth said. That compares to about $3 to $4 per square foot in Stamford and $3 in New Haven.

Developers have required increasingly smaller CRDA loans as rents have climbed, Freimuth said. But rising interest rates and continued supply chain problems with building materials could force that trend in the opposite direction, he warned.

“We still have a disconnect between what it costs to build and what it’s worth upon completion,” Freimuth said. “And that’s less of an issue in New Haven and not really an issue in, let’s say, Stamford.”

Freimuth said New Haven was forced to adapt its economic strategy earlier than Hartford, which has long been sustained by a strong corporate ecosystem and state office buildings. New Haven is as much as a decade ahead of Hartford in terms of economic repositioning, he said.

David Lehman, commissioner of the state Department of Economic and Community Development, noted that New Haven is a growing city, while Hartford lost population over the last decade.

“And I think that’s what’s really driving the demand and there has been more demand for new apartments in New Haven and ones that don’t require any type of subsidy because of that tailwind,” Lehman said. “A lot of that is the nature of the economy in New Haven, which has the eds and meds, the bioscience cluster continuing to grow. Yale continues to expand its presence and funding around the city. You are seeing lots of forces bring people into New Haven and create jobs there and that’s creating tailwinds for the New Haven apartment market.”

Between 2010 and 2020, New Haven’s population grew by about 3%, while Hartford shrank by 3%, according to U.S. Census data.

Lehman said Hartford’s government-assisted drive to build apartments could lead to greater vibrancy, and that the city needs thousands of more units.

“In my mind, you ideally need to put another 10,000 to 20,000 new apartment units downtown,” he said.

Investors happy with returns

Wonder Works Construction Co. and partners have added more than 550 apartments to Hartford in four redeveloped downtown buildings since 2012 under the “Spectra” banner.

Daniel Klaynberg, CEO of Spectra Construction and Development, said occupancy stumbled during the onset of COVID-19, forcing renegotiations with lenders. But the properties have bounced back, pleasing investors and paving the way for additional building, he said.

Klaynberg is working to finalize the purchase of a municipal building at 525 Main St., and a former firehouse at 275 Pearl St. The properties will be remodeled into 78 apartments, with first-floor retail, over the next two to three years, he said.

“Hartford, I think, is positioned well,” Klaynberg said. “I think all these things are going to be positive, and more and more people are going to recognize the city as a place they want to live. We think things will move very positively over the next 10 to 15 years.”

Creating the experience

Matthew Nemerson, who spent five years as New Haven’s development administrator until 2018, also cited Yale University and its medical school as big drivers of New Haven’s economy and apartment developments.

“Between the medical school and university, Yale added about 8,000 jobs over the last eight or nine years,” said Nemerson, who is now vice president of strategic partnerships at Shelton energy technology company Budderfly. “That’s just a lot of people moving into the area.”

New Haven has a well-established network of bars, retail, restaurants and apartments that create the experience Millennials are seeking, Nemerson said. Hartford may be a bit behind that curve, but it could get to a similar place in the future, he said.

But the remote work trend isn’t likely to help Hartford, he added. That trend makes it easier for people to live in established hotspots like New Haven or Stamford, even if they are more distant or costly.

“People over the last 10 years have basically said ‘I would rather live in a smaller, if very expensive, apartment if I can have access to food and fun,’ ” Nemerson said. “Hartford will have to continue to make its urban street life worth living if they are going to not have people living in New Haven and commuting to Hartford.”

Hartford city officials and the CRDA have worked for years to bolster downtown’s vibrancy, including through the creation of the Front Street Entertainment District and minor league baseball stadium. In June, the CRDA began building a sports betting lounge at the XL Center, with the aim of opening later this year.

The city and Hartford Chamber of Commerce, in December, launched the “Hart Lift” program, which gives matching grants of up to $150,000 to help outfit first-floor spaces for retail-oriented businesses and restaurants.

Funded with $6 million in federal COVID-19 relief funds, Hart Lift aims to help the city recapture some of the restaurant and retail activity killed off during the depths of the pandemic.

As of April, the chamber approved 25 grants totaling about $2.5 million.

Klaynberg said the city program has been a tremendous boon. As of December, most of the retail spaces in Spectra’s properties were vacant.

“They all filled up in a matter of months” after the Hart Lift program launched, Klaynberg said.

See related story HERE.

2022 Giving Guide

This special edition informs and connects businesses with nonprofit organizations that are aligned with what they care about. Each nonprofit profile provides a crisp snapshot of the organization’s mission, goals, area of service, giving and volunteer opportunities and board leadership.

Learn more

Subscribe

Hartford Business Journal provides the top coverage of news, trends, data, politics and personalities of the area’s business community. Get the news and information you need from the award-winning writers at HBJ. Don’t miss out - subscribe today.

Subscribe

2024 Book of Lists

Delivering Vital Marketplace Content and Context to Senior Decision Makers Throughout Greater Hartford and the State ... All Year Long!

Read Here-

2022 Giving Guide

This special edition informs and connects businesses with nonprofit organizations that are aligned with what they care about. Each nonprofit profile provides a crisp snapshot of the organization’s mission, goals, area of service, giving and volunteer opportunities and board leadership.

-

Subscribe

Hartford Business Journal provides the top coverage of news, trends, data, politics and personalities of the area’s business community. Get the news and information you need from the award-winning writers at HBJ. Don’t miss out - subscribe today.

-

2024 Book of Lists

Delivering Vital Marketplace Content and Context to Senior Decision Makers Throughout Greater Hartford and the State ... All Year Long!

ABOUT

ADVERTISE

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

0 Comments